Art Movement in the 1980sd 5 Ways Art Communicates

Mail art, also known equally postal art and correspondence fine art, is an artistic movement centered on sending pocket-sized-calibration works through the postal service. It initially adult out of what eventually became Ray Johnson's New York Correspondence School and the Fluxus movements of the 1960s, though it has since developed into a global motion that continues to the present.

Characteristics [edit]

Media commonly used in mail art include postcards, paper, a collage of found or recycled images and objects, rubber stamps, artist-created stamps (called artistamps), and paint, only can also include music, sound art, poetry, or anything that can exist put in an envelope and sent via post. Mail art is considered art in one case information technology is dispatched. Mail artists regularly phone call for thematic or topical mail art for utilize in (often unjuried) exhibition.[1] [2]

Mail artists appreciate interconnection with other artists. The artform promotes an egalitarian fashion of creating that frequently circumvents official art distribution and approval systems such every bit the art market, museums, and galleries. Post artists rely on their alternative "outsider" network equally the principal way of sharing their piece of work, rather than being dependent on the ability to locate and secure exhibition space.[3] [4]

Postal service art can exist seen equally anticipating the cyber communities founded on the Internet.[v] [half dozen]

History [edit]

Ray Johnson'due south invitation to the first post fine art prove, 1970

Artist Edward M. Plunkett has argued that communication-as-fine art-grade is an ancient tradition; he posits (natural language in cheek) that mail service fine art began when Cleopatra had herself delivered to Julius Caesar in a rolled-up carpeting.[seven]

Ray Johnson, the New York Correspondance School, and Fluxus [edit]

The American creative person Ray Johnson is considered to be the first post artist.[1] [8] Johnson'south experiments with fine art in the mail began in 1943, while the posting of instructions and soliciting of activity from his recipients began in the mid-1950s with the mailing of his "moticos", and thus provided postal service art with a blueprint for the costless exchange of art via postal service.[1] [9]

The term "mail art" was coined in the 1960s.[7] In 1962, Plunkett coined the term "New York Correspondence Schoolhouse" to refer to Johnson's activities; Johnson adopted this moniker but sometimes intentionally misspelled it every bit "correspondance."[seven] The deliberate misspelling was characteristic of the playful spirit of the Correspondance School and its actions.[10]

Most of the Correspondance School members are adequately obscure, and the messages they sent, often featuring simple drawings or stickers, frequently instructed the recipient to perform some fairly simple action. Johnson's piece of work consists primarily of letters, often with the addition of doodles and rubber stamped messages, which he mailed to friends and acquaintances. The Correspondance Schoolhouse was a network of individuals who were artists past virtue of their willingness to play along and appreciate Johnson'due south sense of humor. One example of the activities of the Correspondance School consisted in calling meetings of fan clubs, such as one devoted to the actress Anna May Wong. Many of Johnson's missives to his network featured a hand drawn version of what became a personal logo or alter-ego, a bunny caput.[10]

In a 1968 interview, Johnson explained that he found mailed correspondence interesting considering of the limits it puts on the usual back and forth interaction and negotiation that comprises communication between individuals. Correspondence is "a mode to convey a message or a kind of idea to someone which is not verbal; it is not a confrontation of 2 people. Information technology's an object which is opened in privacy, probably, and the message is looked at ... Yous look at the object and, depending on your degree of interest, it very straight gets across to you what is there ..."[11]

In 1970, Johnson and Marcia Tucker organized The New York Correspondence Schoolhouse Exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York, which was the starting time pregnant public exhibition of the mail fine art genre.[1]

On April 5, 1973, Johnson declared the "death" of the New York Correspondance School in an unpublished letter to the Obituary Section of The New York Times and in copies that he circulated to his network. Nonetheless, he continued to practise mail art even after this.[12] [13]

Although much of Johnson's work was initially given away, this hasn't prevented it from attaining a market place value. Andy Warhol is quoted equally saying he "would pay 10 dollars for anything by Johnson."[14]

In his 1973 diagram showing the evolution and scope of Fluxus, George Maciunas included mail art among the activities pursued past the Fluxus artist Robert Filliou.[15] Filliou coined the term the "Eternal Network" that has become synonymous with mail service art.[16] Other Fluxus artists have been involved since the early on 1960s in the creation of artist's stamp stamps (Robert Watts, Postage Dispenser, 1963), postcards (Ben Vautier, The Postman'south Pick, 1965: a postcard with a different accost on each side) and other works connected to the postal medium.[ citation needed ] "Indeed, the mail art network counts many Fluxus members among its earliest participants. While Johnson did not consider himself directly as a member of the Fluxus schoolhouse, his interests and attitudes were consistent with those of a number of Fluxus artists.[10] [xi]

Post art stamp and envelope with official Filly Anniversary postmark – Chuck Welch, aka Cracker Jack Kid, 1984

1970s and 1980s [edit]

In the 1970s, the practice of mail art grew considerably, providing a cheap and flexible channel of expression for cultural outsiders. It was particularly widespread where state censorship prevented a free apportionment of alternative ideas, as in certain countries backside the Iron Curtain or in South America.[17]

The growth of a sizable mail art community, with friendships built-in out of personal correspondence and, increasingly, mutual visits,[xviii] led in the 1980s to the arrangement of several festivals, meetings and conventions where networkers could run across, socialize, perform, exhibit and programme farther collaborations. Amongst these events were the Inter Dada Festivals organized in California in the early 1980s[19] and the Decentralized Post Art Congress of 1986.[xx]

In 1984 curator Ronny Cohen organized an exhibition for the Franklin Furnace, New York, called "Mail Fine art Then and Now."[21] The exhibition was to accept an historical attribute also equally showing new mail service art, and to mediate the two aspects Cohen edited the material sent to Franklin Furnace, breaking an unwritten merely commonly accustomed custom that all works submitted must exist shown. The intent to edit, interpreted as censorship, resulted in a two-part panel discussion sponsored by Artists Talk on Fine art (organized by postal service artist Carlo Pittore and moderated by art critic Robert C. Morgan) in February of that twelvemonth, where Cohen and the mail artists were to argue the issues.

The nighttime preceding the second panel on February 24, Carlo Pittore, John P. Jacob, Chuck Welch a.k.a. CrackerJack Child, David Cole and John Held Jr. crafted a statement asking Dr. Cohen to step down every bit the panel moderator. Welch delivered the statement whereby Dr. Cohen was asked to remain on the console only forfeit her correct to serve every bit moderator. Instead of remaining, Cohen chose to leave the upshot. After some give and take with both panelists and audience, Dr. Cohen left, saying, "Take fun, boys." Her entourage walked out with her during the ensuing melee.[22]

The excluded works were ultimately added to the exhibition by the staff of the Franklin Furnace, but the events surrounding information technology and the panels revealed ideological rifts within the postal service fine art community. Simultaneously fanning the flames and documenting the extent to which information technology was already dominated past a small, mostly male, coterie of artists, the discussions were transcribed and published past panelist John P. Jacob in his short-lived mail art zine PostHype.[23] In a alphabetic character to panelist Marker Bloch, Ray Johnson (who was not a panelist) commented on the reverse-censorship and sexism of the event.[24]

The rise of mail art meetings and congresses during the late 80s, and the joint of various "isms" proclaimed past their founders as movements within mail art, were in office a response to fractures made visible by the events surrounding the Franklin Furnace exhibition.[25] Fifty-fifty if "tourism" was proposed satirically as a new movement by H.R. Fricker, a Swiss mail service artist who was one of the organizers of the 1986 Mail Fine art Congress, nevertheless post art in its pure form would continue to office without the personal meeting betwixt so-called networkers.[xx]

In the mid-1980s, Fricker and Bloch, in a bilingual "Open Letter To Everybody in the Network" [26] stated, "1) An important role of the exhibitions and other group projects in the network is: to open up channels to other human beings. two) Afterward your exhibition is shown and the documentation sent, or later you have received such a documentation with a list of addresses, use the channels! 3) Create person-to-person correspondence... iv) Y'all have your own unique energy which you tin can give to others through your work: visual audio, verbal, etc. 5) This energy is best used when it is exchanged for energy from another person with the same intentions. 6) the power of the network is in the quality of the direct correspondence, not the quantity." The manifesto concludes, "We have learned this from our own mistakes."[27]

1990s and the bear upon of the Internet era [edit]

American mail-artist David Horvitz (active since the 2000s) meets Brazilian mail artist Paulo Bruscky (active since the 1970s) in Berlin, Frg in November 2015.

In 1994, Dutch mail service creative person Ruud Janssen began a series of postal service-interviews which became an influential contribution in the field of postal service art.[28]

By the 1990s, post fine art's peak in terms of global postal activities had been reached, and mail artists, aware of increasing postal rates, were beginning the gradual migration of collective art projects towards the web and new, cheaper forms of digital communication.[29] The Internet facilitated faster dissemination of postal service art calls (invitations) and precipitated the involvement of a large number of newcomers.[ citation needed ]

Philosophy and norms of the mail artist network [edit]

In spite of the many links and similarities between historical avant-garde, culling art practices (visual poetry, copy fine art, creative person'due south books) and mail art, one aspect that distinguishes the creative postal network from other artistic movements, schools or groups (including Fluxus) is the way it disregards and circumvents the commercial art market.[5] Whatsoever person with access to a mailbox can participate in the postal network and exchange free artworks, and each post artist is free to make up one's mind how and when to answer (or not answer) a piece of incoming mail. Participants are invited past network members to take part in commonage projects or unjuried exhibitions in which entries are not selected or judged. While contributions may be solicited effectually a item theme, work to a required size, or sent in by a borderline, mail service art more often than not operates within a spirit of "anything goes."[8]

The postal service fine art philosophy of openness and inclusion is exemplified past the "rules" included in invitations (calls) to postal projects: a postal service fine art testify has no jury, no entry fee, in that location is no censorship, and all works are exhibited.[8] The original contributions are not to exist returned and remain the holding of the organizers, simply a catalogue or documentation is sent free to all the participants in commutation for their works. Although these rules are sometimes stretched, they take more often than not held up for iv decades, with simply small-scale dissimilarities and adjustments, like the occasional requests to avoid works of explicit sexual nature, calls for projects with specific participants, or the recent trend to display digital documentation on blogs and websites instead of personally sending printed paper to contributors.[30] [31]

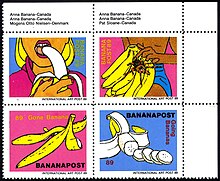

BananaPost '89 artistamps past Anna Banana, 1989

Mail art has been exhibited in alternative spaces such as individual apartments, municipal buildings, and shop windows, too as in galleries and museums worldwide.[3] Post art shows, periodicals, and projects represent the "public" side of postal networking, a exercise that has at its core the direct and individual interaction between the private participants. Post artists value the process of exchanging ideas and the sense of belonging to a global community that is able to maintain a peaceful collaboration beyond differences of linguistic communication, religion and credo; this is one aspect that differentiates the mail service art network from the earth of commercial picture postcards and of simply "mailed art."[32]

A post artist may have hundreds of correspondents from many different countries, or build a smaller core circumvolve of favorite contacts. Post art is widely skillful in Europe, Northward and S America, Russia, Australia and Nihon, with smaller numbers of participants also in Africa, and Communist china.[ citation needed ] In addition to being kept by the recipient, postal service art archives accept attracted the interest of libraries, archives, museums, and individual collectors.[five] Or, the works may be 'worked into' and recycled back to the sender or to another networker.

Mail art envelope from H.R. Fricker, 1990

Ray Johnson suggested (with a pun) that "mail art has no history, only a present", and mail artists have followed his playful attitude in creating their own mythologies.[33] Parody art movements like neoism and plagiarism take challenged notions of originality, every bit have the shared pseudonymous names Monty Cantsin and Karen Eliot, which were proposed for series use by anyone.[34] Semi-fictional organizations have been set up and virtual lands invented, imaginary countries for which artistamps are issued.[35] Furthermore, attempts accept been fabricated to document and ascertain the history of a complex and underestimated phenomenon that has spanned five decades. Various essays, graduate theses, guides and anthologies of postal service art writings take appeared in print and on the Internet, often written by veteran networkers.[32] A sub-grouping of envelope art has its genesis in the Grateful Expressionless Ticket Service. Looking to help their fans avoid the high fees that are generated past national ticket services the Grateful Dead started their own service, commonly referred to as mail club. At some point fans started decorating their envelopes with art. Some for art's sake, others to take hold of the attention of the people that dole out tickets in hope of better seats.

Canvas of artistamps by Piermario Ciani, c. 1995

Media and artistic practices in the creation of mail artworks [edit]

Because the democratic ethos of mail art is one of inclusion, both in terms of participants ('anyone who can afford the postage') and in the scope of fine art forms, a broad range of media are employed in creation of mail artworks. Certain materials and techniques are commonly used and often favored by mail service artists due to their availability, convenience, and ability to produce copies.

Rubberstamps and artistamps [edit]

Mail fine art rubber stamps by Jo Klafki (left) and Marker Pawson (right), 1980s

Mail art has adopted and appropriated several of graphic forms already associated with the postal system. The prophylactic stamp officially used for franking mail, already utilized past Dada and Fluxus artists, has been embraced by mail service artists who, in addition to reusing fix-made rubber stamps, have them professionally fabricated to their ain designs. They too cleave into erasers with linocut tools to create handmade ones. These unofficial rubber stamps, whether disseminating post artists' letters or simply announcing the identity of the sender, aid to transform regular postcards into artworks and brand envelopes an of import part of the mail art experience.[32]

Carved eraser print by Paul Jackson, aka Art Nahpro, c. 1990

Mail art has too appropriated the postage postage stamp as a format for individual expression. Inspired by the case of Cinderella stamps and Fluxus faux-stamps, the artistamp has spawned a vibrant sub-network of artists dedicated to creating and exchanging their own stamps and stamp sheets.[36] Artist Jerry Dreva of the conceptual fine art group Les Petits Bonbons created a set of stamps and sent them to David Bowie who so used them equally the inspiration for the encompass of the single "Ashes to Ashes" released in 1980.[37] Artistamps and rubber stamps, accept become of import staples of mail artworks, particularly in the enhancement of postcards and envelopes.[35] The most important anthology of rubberstamp fine art was published by the creative person Hervé Fischer in his volume Art and Marginal Communication, Balland, Paris, 1974 - in French, English and German, to note likewise the catalog of the exhibition "Timbres d'artistes", Published of Musée de la Poste, Paris, 1993, organized past the French artist Jean-Noël Laszlo - in French, English language.

Envelopes [edit]

Some mail artists lavish more attention on the envelopes than the contents within. Painted envelopes are one-of-a-kind artworks with the handwritten accost becoming role of the work. Stitching, embossing and an array of cartoon materials can all be establish on postcards, envelopes and on the contents inside.[38]

Printing and copying [edit]

Printing is suited to mail artists who distribute their work widely. Various printmaking techniques, in addition to rubber stamping, are used to create multiples. Re-create fine art (xerography, photocopy) is a mutual practice, with both mono and colour copying being extensively used within the network.[two] Ubiquitous 'add & pass' sheets that are designed to be circulated through the network with each artist adding and copying, concatenation-letter fashion, have also received some unfavorable criticism.[ co-ordinate to whom? ] However, Xerography has been a key technology in the creation of many short-run periodicals and zines almost post art, and for the printed documentation that has been the traditional project culmination sent to participants. Inkjet and laserprint computer printouts are also used, both to disseminate artwork and for reproducing zines and documentation, and PDF copies of paperless periodicals and unprinted documentation are circulated by email. Photography is widely used every bit an art course, to provide images for artistamps and rubber stamps, and within printed and digital magazines and documentation,[32] while some projects have focused on the intersection of mail art with the medium itself.[39]

Lettering and language [edit]

Lettering, whether handwritten or printed, is integral to mail art. The written word is used as a literary art class, too equally for personal letters and notes sent with artwork and recordings of the spoken word, both of poesy and prose, are also a part of the network.[2] Although English language has been the de facto language, because of the movement's inception in America, an increasing number of mail service artists, and mail artist groups on the Internet, now communicate in Breton, French, Italian, High german, Spanish, and Russian.[ commendation needed ]

Other media [edit]

In addition to appropriating the stamp stamp model, mail artists have alloyed other design formats for printed artworks. Artists' books, decobooks and friendship books, banknotes, stickers, tickets, artist trading cards (ATCs), badges, food packaging, diagrams and maps have all been used.

Cover of Kairan mail art zine, edited past Gianni Simone, aka Johnnyboy, 2007

Post artists routinely mix media; collage and photomontage are pop, affording some mail fine art the stylistic qualities of popular art or Dada. Mail artists often use collage techniques to produce original postcards, envelopes and work that may be transformed using re-create art techniques or computer software, and then photocopied or printed out in limited editions.

Printed matter and ephemera are oft circulated among postal service artists, and after artistic treatment, these common items enter into the mail art network.[ii] Pocket-sized assemblages, sculptural forms or establish objects of irregular shapes and sizes are parceled up or sent unwrapped to deliberately tease and exam the efficiency of the postal service. Mailable faux fur ("Hairmail") and Astroturf postcards were circulated in the belatedly 1990s.[38]

Having borrowed the notion of intermedia from Fluxus, mail service artists are often active simultaneously in several different fields of expression. Music and sound art take long been celebrated aspects of mail fine art, at starting time using cassette tape, then on CD and as audio files sent via the Internet.[40]

Performance art has also been a prominent facet, particularly since the advent of mail fine art meetings and congresses. Performances recorded on picture show or video are communicated via DVD and movie files over the internet. Video is likewise increasingly existence employed to document postal service art shows of all kinds.[41]

Quotations [edit]

"Correspondence fine art is an elusive art course, far more than variegated by its very nature than, say, painting. Where a painting always involves pigment and a support surface, correspondence art can appear as any one of dozens of media transmitted through the postal service. While the vast bulk of correspondence art or mail art activities take place in the mail, today's new forms of electronic communication blur the edges of that forum. In the 1960s, when correspondence art get-go began to blossom, most artists found the mail service to be the well-nigh readily available - and to the lowest degree expensive - medium of exchange. Today's micro-computers with modern facilities offer anyone calculating and communicating power that two decades ago were available only to the largest institutions and corporations, and simply a few decades previous weren't available to anyone at any price." - Ken Friedman[42]

"Cultural exchange is a radical act. Information technology can create paradigms for the reverential sharing and preservation of the world's water, soil, forests, plants and animals. The ethereal networker aesthetic calls for guiding that dream through activeness. Cooperation and participation, and the celebration of art equally a birthing of life, vision, and spirit are first steps. The artists who see each other in the Eternal Network take taken these steps. Their shared enterprise is a contribution to our mutual future." - Chuck Welch[32]

"The purpose of mail art, an activity shared past many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical advice betwixt artists and common people in every corner of the world, to divulge their piece of work outside the structures of the art market and exterior the traditional venues and institutions: a costless advice in which words and signs, texts and colours human action like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction." - Loredana Parmesani[43]

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Mail service Art". Collection: MOCA's First Thirty Years. MOCA: The Museum of Gimmicky Fine art, Los Angeles. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Mail Art". Digital Collections, UB Libraries. University at Buffalo, The State Academy of New York. Retrieved eleven April 2013.

- ^ a b "Mail Art @ Oberlin". Oberlin College Fine art Library. Oberlin College & Conservatory. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Richard Kostelanetz; H. R. Brittain (2001). A Lexicon of the Avant-gardes. Routledge. p. 388. ISBN978-0-415-93764-one.

- ^ a b c "About John Held Jr. in the Spark episode "The Fine Art of Collecting"". Spark. KQED. 2004. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bloch, Mark (Summer 2000). "Communities Collaged: Mail Fine art and The Net". New Observations, No. 126, the Art is in the Postal service(ing) . Retrieved fifteen Jan 2022.

- ^ a b c Plunkett, Edward M. (1977). "The New York Correspondence School". Fine art Journal (Spring). Retrieved eleven April 2013.

- ^ a b c Phillpot, Clive (1995). Chuck Welch (ed.). Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology. Canada: Academy of Calgary Press. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Francesco Vincitorio, "Informalista o videoartista? Le tendenze artistiche dagli anni '40 advert oggi", L'Espresso n.44, seven November 1982[ full commendation needed ]

- ^ a b c Danto, Arthur C. (March 29, 1999). "Correspondance School Fine art". The Nation . Retrieved 11 Apr 2013.

- ^ a b "Oral history interview with Ray Johnson, 1968 Apr. 17". Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved eleven April 2013.

- ^ "Ray Johnson mail art to Lucy R. Lippard, 1965 June 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Ray Johnson Biography". Ray Johnson Manor. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Stewart Dwelling, The Assault On Culture, Aporia Printing & Unpopular Books, London 1988[ full citation needed ]

- ^ Hendricks, Jon (1988). Fluxus Codex, New York: Harry N. Abrams, pp 329–333. ISBN 978-0-8109-0920-v

- ^ Bloch, Mark. "An Authentik and Historikal Discourse On the Phenomenon of David Zack, Postal service Creative person". In Istvan Kantor (ed.). Amazing Letters: The Life and Art of David Zack . Retrieved eleven April 2013.

- ^ Jacob, John (1985). "East/West: Mail Art & Censorship". PostHype. iv (1). ISSN 0743-6025.

- ^ Lloyd, Ginny (1981). "The Mail service Art Customs in Europe". Umbrella Magazine. 5 (1).

- ^ Ross, Janice (August 26, 1984). "A gleefully rebellious festival of dada". Oakland Tribune. Art: The Tribune Agenda. Retrieved eleven April 2013.

- ^ a b "Hans-Reudi Fricker". Mail Art @ Oberlin. Oberlin College & Conservatory. Archived from the original on iii September 2013. Retrieved 11 Apr 2013.

- ^ "Mail Art From 1984 Franklin Furnace Exhibition". Franklin Furnace. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Heisler, Faith (1984). "International MailArt--Part 2: The New Cultural Strategy". Women Artists News. Vol. nine, no. four. p. 18.

- ^ Jacob, John (1984). "Mailart: A Partial Anatomy". PostHype. 3 (1). ISSN 0743-6025.

- ^ Mark, Bloch. "Ray Johnson's letter to me afterwards the event, questioning the issue of sexism". panmodern.com. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Jacob, John (1987). The Coffee Table Book of Mail Art: The Intimate Letters of J.P. Jacob, 1981 - 1987. New York: Riding Beggar Press.

- ^ Bloch, Marker and Fricker, Hans Ruedi."Phantastische Gebete Revisited" in Panmag International Magazine half-dozen, ISSN 0738-4777, Feb 1984. pg. 8.

- ^ Röder, Kornelia "H. R. Fricker, Mail Art and Social Networks," HR Fricker: Conquer the Living Rooms of the World, Kunstmuseum Thurgau, Warth, Switzerland: Edition Fink, 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Ruud Janssen, Mail-Interviews, Tilburg 1994–2001

- ^ Guy Bleus (Ed.), Re: The E-Mail-Fine art & Internet-Art Manifesto, in: Eastward-Pêle-Mêle: Electronic Postal service-Art Netzine, Vol.Three, n° ane, T.A.C.-42.292, Hasselt, 1997.

- ^ "Guy Bleus: Post Art Initiation – Mail service Art Chro no logy".

- ^ "Bleus | Exploring postal service-art". 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d due east Welch, C. (1995). Eternal network: A mail art anthology. Calgary, Alta: Univ. of Calgary Printing.

- ^ Thou., De Salvo, Donna; Catherine., Gudis (1999). Ray Johnson : correspondences. Wexner Center for the Arts. p. 81. ISBN2080136631. OCLC 43915838.

- ^ C. Carr (9 April 2012). On Edge: Performance at the End of the Twentieth Century. Wesleyan University Printing. pp. 105–. ISBN978-0-8195-7242-iv.

- ^ a b Frank, Peter, E.F. Higgins III, Rudolf Ungváry. "Postal Modernism: Artists' Stamps and Stamp Images." World Art Mail service, Artpool Annal, Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, April 1982 (pp. 1–4)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-05-26. Retrieved 2015-05-26 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link) Belgian Post, Guy Bleus & Jean Spiroux, Journée du Timbre: Mail-Art, 2003. - ^ Griffin, Roger. "Scary Monsters". Bowie Golden Years.

- ^ a b Elving, Bell (April xxx, 1998). "Pushing The Envelope". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jacob, John (1984). The International Portfolio of Artists Photography. New York: Riding Beggar Printing.

- ^ Christoph Cox; Daniel Warner (i September 2004). Audio Culture: Readings in Mod Music. Continuum. pp. lx–. ISBN978-0-8264-1615-5.

- ^ "The Techniques". Mail-Art:The Forum. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Friedman, Ken (1984). Wilson, Martha (ed.). "Mail art history: the Fluxus factor". FLUE. Franklin Furnace. four (3–4).

- ^ Loredana Parmesani, text under the entry "Poesia visiva", in L'arte del secolo - Movimenti, teorie, scuole e tendenze 1900–2000, Giò Marconi - Skira, Milan 1997[ total citation needed ]

Further reading

Postal service art by A.D. Eker (Thuismuseum), 1985

- Thomas Bey William Bailey, Unofficial Release: Self-Released And Handmade Audio In Mail service-Industrial Order, Belsona Books Ltd., 2012

- Vittore Baroni, Arte Postale: Guida al network della corrispondenza creativa, Bertiolo 1997

- Vittore Baroni, Postcarts - Cartoline d'artista, Rome 2005

- Tatiana Bazzichelli, Networking: The Net as Artwork, Aarhus 2008

- Mark Bloch, Communities Collaged: Postal service Fine art and The Net, New Observations, No. 126, The Art is in the Mail(ing), New York, 2000

- Ina Blom, The Name of the Game. The Postal Functioning of Ray Johnson, Oslo/Kassel/Sittard, 2003

- Ulises Carrión, "El Arte Correo y el Gran Monstruo", Tumbona ediciones, Mexico, 2013

- Michael Crane & Mary Stofflet (editors), Correspondence Art: Sourcebook for the Network of International Postal Art Activeness, San Francisco 1984

- Donna De Salvo & Catherine Gugis (editors), Ray Johnson: Correspondences, Paris-New York 1999

- Fernando García Delgado, El Arte Correo en Argentina, Vortice Argentine republic Ediciones., 2005

- Franziska Dittert, Mail Art in der DDR. Eine intermediale Subkultur im Kontext der Avantgarde, Berlin 2010

- James Warren Felter, Artistamps – Francobolli d'artista, Bertiolo 2000

- Hervé Fischer, Art et Advice Marginale: Tampons d'Artistes, Paris 1974

- H. R. Fricker, I Am A Networker (Sometimes), St. Gallen 1989

- Religion Heisler International Mail Art--Part II: The New Cultural Strategy, Women Artists News, 1984

- John Held Jr., L'arte del timbro - Rubber Stamp Fine art, Bertiolo 1999

- John Held Jr., Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography, Metuchen 1991

- Ramzi Turki, (préf. d'Olivier Lussac), L'e-mail-art, création d'une nouvelle forme artistique, Paris, Édition Edilivre, 2015

- Jon Hendricks, Fluxus Codex, New York 1988

- Jennie Hinchcliff & Carolee Gilligan Wheeler, Good Postal service Day: A Primer for Making Eye-Popping Postal Art, Quarry 2009

- John P. Jacob, The Coffee Table Volume of Mail Fine art: The Intimate Messages of J.P. Jacob, 1981-1987, Riding Beggar Press, New York, 1987

- John P. Jacob, Mail Art: A Partial Anatomy, PostHype book three number 1, New York, 1984

- Jean-Noël Laszlo (editor), Timbres d'Artistes, Musée de la Poste, Paris 1993

- Giovanni Lista, L'Fine art Postal Futuriste, Paris 1979

- Ginny Lloyd, Blitzkunst: have you ever done anything illegal in order to survive as an artist?, Kretschmer & Grossmann, Frankfurt, 1983

- Ginny Lloyd, Inter DADA 84: Truthful DADA Confessions, Jupiter 2014

- Ginny Lloyd, The Storefront: A living art project, San Francisco, 1984

- Ginny Lloyd, Tour '81 Sketch BOOK, TropiChaCHa Press, Jupiter, 1981 - 2011

- Ginny Lloyd, Women in the Artistamp Spotlight, Jupiter 2012

- Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, Artecorreo – artistas invisibles en la ruddy postal, La Plata, Argentina 2010

- Joni K. Miller & Lowry Thompson, The Rubber Postage stamp Album, New York 1978

- Sandra Mizumoto Posey, Condom Soul: Safety Stamps and Correspondence Fine art, Jackson 1996

- Géza Perneczky, The Magazine Network: The Trends of Alternative Art in the Light of Their Periodicals 1968–1988, Köln 1993

- Jean-Marc Poinsot, Mail Art: Communication A Altitude Concept, Paris 1971

- Kornelia Röder, Topologie und Funktionsweise des Netzwerkes der Mail Fine art, Bremen 2008

- Günther Ruch (editor), MA-Congress 86, Out-press, Geneva 1987

- Craig J. Saper, Networked Art, Minneapolis-London 2001

- Renaud Siegmann, Mail Fine art: Fine art postal – Art postè, Paris 2002

- Chuck Welch (editor), Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, Calgary 1995

- Chuck Welch, Networking Currents: Contemporary Mail Fine art Subjects and Issues, Boston 1986

- Friedrich Winnes-Lutz Wohlrab, Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994

External links [edit]

- Post Art-Archive at the Staatliches Museum Schwerin, 30,000 pieces

- "You lot've Got Mail Art: Discovering John Held Jr.'s Role every bit Librarian and Post Artist," Athenaeum of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution

- E.F.Higgins Three - Doo Da Postage Works

- Post fine art digital collection from the University at Buffalo Libraries

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mail_art

0 Response to "Art Movement in the 1980sd 5 Ways Art Communicates"

Post a Comment